Inside Orange County’s Ronald Reagan Federal Courthouse on Feb. 23, the 4-year-old jailhouse-informant scandal created by the deceitful duo of District Attorney Tony Rackauckas and Sheriff Sandra Hutchens took another casualty: the U.S. Attorney’s office inside the Department of Justice (DOJ). But the trauma isn’t worthy of sympathy. Sadly, the Santa Ana DOJ branch is responsible for enlarging a festering criminal-justice cesspool.

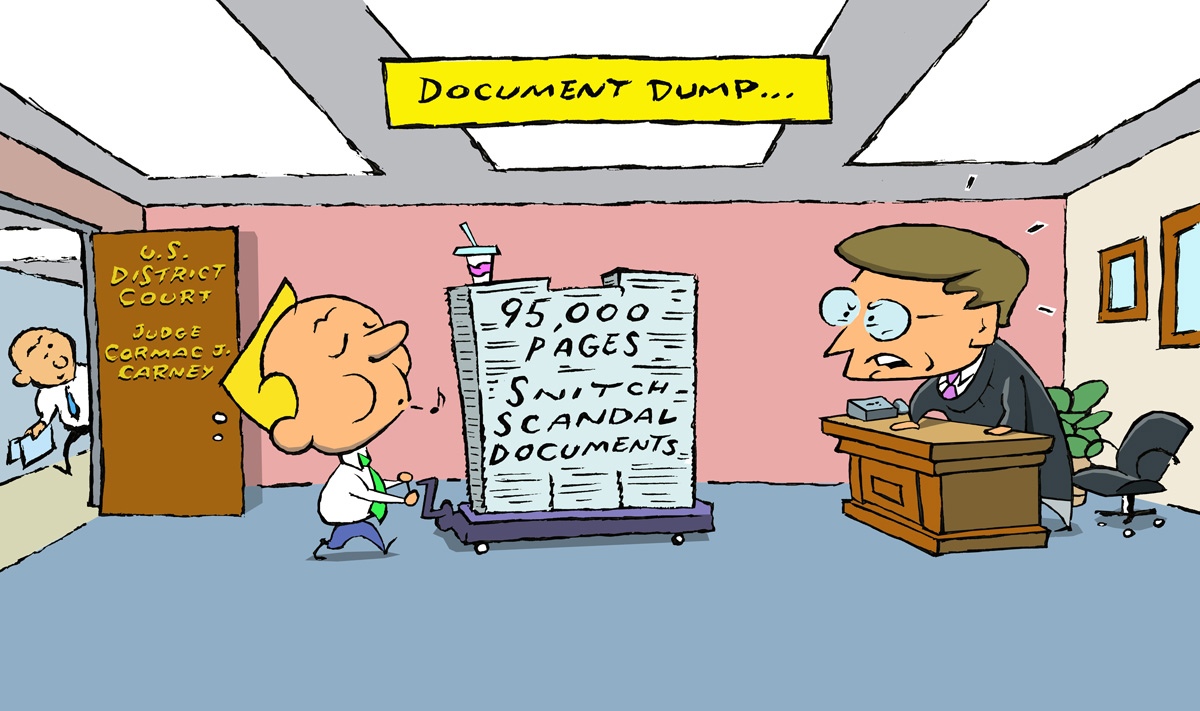

Just two working days before the suspicious case of USA v. Joseph Martin Goveywas scheduled for trial, federal prosecutor Bradley Marrett handed U.S. District Court Judge Cormac J. Carney 20,000 supposedly top-secret pages of documents related to the snitch scandal that Govey inadvertently helped to expose.

On the verge of being either obnoxious or ignorant, Marrett laughably wanted the judge to drop everything, miraculously speed-read the pages, then keep the relivent evidence secret from Timothy Scott, Govey’s San Diego-based defense lawyer. Thanks to the DOJ’s foot-dragging, Scott faced a similar herculean task, finally receiving in recent weeks 75,462 pages of documents he’d been seeking for several months.

An unamused Carney labeled the government’s moves a trial-eve “document dump” and said he was “just dumbfounded” and “absolutely baffled” by federal prosecutors entangling themselves in Rackauckas/Hutchens corruption.

“You hit me with [20,000 pages] yesterday afternoon,” Carney told Marrett. “I have to make a decision of that magnitude, over 20,000 pages of documents before a trial starts [in two days]. And you file it under seal and Mr. Scott and Mr. Govey don’t even get to see the motion . . . How realistic or practical is that?”

The judge was particularly perturbed by federal prosecutors’ assertion that his decision about whether to release documents in a rush at the government’s making could risk the lives of snitches as he balanced the defendant’s right to a fair trial.

As a result, Carney dismissed all charges, including drug- and counterfeit-possession counts, against Govey, who was freed after spending seven months in custody. He also pondered why federal prosecutors would interfere with their own agency’s investigation of rampant Orange County Sheriff’s Department corruption.

“I think it was all plastered over OC Weekly,” the judge said.

For snitch-scandal deniers, this latest courthouse shocker will require additional fact-omitting mental gymnastics. As improbable as it may seem, Govey—a onetime member of the Public Enemy Number One Death Squad (PEN1) gang—symbolizes it’s not just the street criminals who sidestep ethical lines and legal prohibitions. Twice now, overzealous government officials have seen their cases against him crumble.

In September 2014, Rackauckas’ office decided to drop charges of solicitation of murder, attempted murder and street terrorism rather than comply with a judge’s order to surrender long-buried sheriff’s department TRED records. There’s a reason Hutchens’ agency fought so hard for years to keep them hidden. The TREDs contain proof of deputies’ illegal tactics, including falsifying reports, destroying exculpatory evidence, committing perjury and, in violation of a monumental U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Massiah, using jailhouse informants to question charged, pretrial defendants about their cases without their lawyers present. We later learned officers used snitches Jason Fenstermacher and Alexander Frosio for such schemes against Govey. For example, a TRED entry shows deputies ordered Frosio to “produce information” and pretend there’d been no government enticement, or risk physical assault while incarcerated.

That case smelled from the outset. A Huntington Beach Police Department informant sold Govey illegal narcotics, then alerted a SWAT team to move in on him and his passenger, Shirley Williams. Within a year, authorities got another informant to declare the defendant wanted Deputy District Attorney Jim Mendelson murdered.

Govey, who says cops have “a vendetta” against him, remained free for nearly two years when, in June 2017, sheriff’s deputies claim they accidentally raided his Anaheim home near Disneyland and found 37 grams of methamphetamine. He said the drugs were for personal use, but Rackauckas bolstered the severity of the case by accusing him of intending to peddle the meth. After about six weeks, an epiphany struck the DA. He could maximize Govey’s punishment exposure by closing his state case, nudging the U.S. Attorney’s office to take over and watching his target get a whopping 10-year federal prison sentence.

To appreciate the significance of that aim, consider Orange County law enforcement’s treatment of Bryan Jason Goldstein. Six months before Govey’s arrest, the Newport Beach Police Department and sheriff’s deputies found Goldstein at a Beach Boulevard shopping plaza in possession of 55 grams of meth—18 more grams than Govey—plus 2 grams of heroin, five Xanax pills, marijuana, 76 plastic baggies, a narcotics pipe and scales. Goldstein also tried to run over officers, according to police records. Despite a record of 16 prior felonies, including weapons charges, he received a sweetheart deal, resulting in only several months in the local lockup.

Why the disparity?

Goldstein is a veteran snitch for cops.

Govey is a longtime target of snitches and cops.

“What I don’t understand is why did the feds take this case?” asked Carney. “Why would you compriomise a federal investigation into the OC sheriff’s department? Why would you drag the federal government into this informant scandal?”

But the government’s plan to take down Govey didn’t go as expected. When the matter landed in his court, Carney expressed bafflement. The 2003 President George W. Bush appointee said he’d never seen such a small amount of dope prosecuted in this manner. He’d also previously rejected attempts to keep Govey’s connection to the snitch scandal out of the federal case, wondering aloud in open court if law-enforcement “retaliation” was a factor a future jury should consider.

Before dismissing the case with prejudice at the Feb. 23 hearing, the judge scolded federal prosecutors. The last-minute massive document dump had not only unfairly hampered Scott’s defense preparation, but it also represented an intentional trampling of the defendant’s constitutional right to a fair trial, he said.

“I believe Mr. Govey’s 6th Amendment rights to a speedy trial, compulsory process and confrontation have been been denied by the government’s failure to timely disclose material documents that Mr. Govey needs to expose percipient witnesses’ bias against him and to attack their character for truthfulness,” Carney said.

The mess is larger than one case. With the latest Govey dismissal, government cheating involving informants now sits at 18 cases. The California Attorney General’s office, which is supposed to police law-enforcement corruption, shortchanged Scott Sanders, the assistant public defender who discovered the scandal in People v. Scott Dekraai, which was presided over by Judge Thomas M. Goethals. Though the office claimed it possessed 25,000 snitch records, it handed Sanders almost none, hindering his ability to find additional wrongdoing.

“It is astounding what has emerged from Joseph Govey’s case,” Sanders told the Weekly. “It fundamentally changes our understanding of the scope of this scandal. We had four years of informant litigation in Dekraai, a death-penalty case, and the Attorney General gave us just 11 pages at a moment right before Judge Goethals dismissed the death penalty. In a simple meth case, prosecutors gave Govey 75,000 pages out of what they now say is more than 10 times that amount.”

Why should anyone care about that hidden cache?

“Informants are the most dangerous witnesses in terms of perpetuating wrongful convictions, and these records are being withheld,” he added. “We have a broken system.”

No comments:

Post a Comment