Before letting police officers answer questions on the witness stand about possible crimes, prosecutors usually establish credibility by eliciting their work experience. Most cops impressively recall the day, month and year of every promotion, even in multidecade careers. But recently inside a Little Saigon-area courtroom, Orange County Sheriff’s Department (OCSD) deputy Cyril Foster appeared to suffer severe amnesia in one of his cases, People v. Jordan Prinzi. From initial appearances Prinzi looked non-controversial. Foster testified as deputy district attorney Sarah Rahman’s lone witness at the March preliminary hearing and confidently recounted events surrounding his arrest of the defendant for purportedly selling heroin on Aug. 21, 2017, at Costa Mesa’s Vagabond Inn. However, trouble occurred three-quarters through direct examination, when the 10-year deputy spent minutes unable to remember the four uncomplicated sentences of the Miranda warning.

“Sorry, I’m a little nervous,” an exasperated Foster said.

The cause of the deputy’s angst isn’t a mystery: Scott Sanders—the public defender who’d uncovered the nationally infamous jailhouse-informant scandal that exposed corruption inside Sandra Hutchens’ OCSD and Tony Rackauckas’ Orange County district attorney’s office (OCDA)—sat beside Prinzi at the defense table. Eager to begin cross-examination, Sanders believed the government’s case wasn’t as open-and-shut as Rahman implied. Besides, Foster appreciated his luck up to this day.

Prior to investigating narcotics activity, the deputy worked in OCSD’s Special Handling Unit, which was ground zero for the snitch scandal. Sanders overcame Rackauckas’ and Hutchens’ five-year plot to derail him and proved in People v. Scott Dekraai that deputies routinely not only violated the constitutional rights of charged, pretrial defendants, but also hid exculpatory evidence and committed perjury. Foster had been on the verge of being grilled under oath in mid-2017 when Superior Court Judge Thomas M. Goethals, who presided in Dekraai, announced he didn’t need to hear any more evidence of corruption to know it existed.

OCSD and OCDA officials couldn’t mask their glee when, per standard public defender agency duty rotations, Sanders got transferred in February from major central courthouse tasks to manage his office’s operations at the traffic-infraction- and misdemeanor-heavy West Court outpost. They hoped themselves finally out of his reach. But, as Foster can verify, they were mistaken.

During cross-examination, Sanders asked a series of questions calling on the deputy to recall the general dates of his promotions. Foster played dumb, feigning he couldn’t remember key career moments in 2016, 2017 and even this year. He said he didn’t know if he’d been in particular units for two weeks or seven years. He had difficulty recollecting basic tasks for assignments. In less than a year, this deputy—who looks to be in his early 40s, not late 90s—testified in just five drug sales cases and couldn’t recall when the trials happened or the names of four of the defendants.

Foster, his lawyer and the OCSD leadership—represented by Commander Bill Baker, who watched Prinzi proceedings—certainly were none-too-happy when Judge Jeremy Dolnick allowed Sanders to briefly probe the agency’s scam of placing former Special Handling deputies under internal affairs (IA) investigations in an effort to convince the California Attorney General’s office and U.S. Department of Justice that OCSD was addressing its illegal-informant actions by going after supposedly “rogue” officers in that unit. Foster, who had inexplicably been promoted to investigator while his internal review was pending and was fully appreciating his role in the scam, turned to his tattered memory as a feeble escape route, claiming it had robbed him of his ability to say when or if the fake IA investigation had ended.

Having established Foster’s memory issues, Sanders pounced. He got the deputy to admit that though his practice is to record all suspect interrogations, he allegedly forgot to bring his digital recorder to the Prinzi raid and didn’t think to use his cellphone’s recorder app. Foster also insisted he’d forgotten to ask any of his five accompanying officers for their recorders or phones. “I made a mistake,” he testified, when pushed for an explanation. “They’re bad mistakes.”

Nonetheless, the deputy proceeded with the key interview, failed to take written notes, collected the narcotics, left Prinzi at the hotel, went home, slept, and the next morning crafted a report outlining the key to elevating the government’s case from simple possession by claiming the defendant freely admitted to selling drugs, a far worse felony, after being Mirandized.

Based on his own investigation, Sanders doesn’t believe the deputy’s story. He confronted Foster about how he could write a detailed, five-page report hours later with no notes or recordings. “Was it just your memory?” he asked.

The deputy replied, “Yes, sir.”

In a fair criminal-justice system, prosecutors and defense lawyers are allowed to explore the credibility of witnesses and expose any history of moral turpitude that might undermine their claims. In recent years, this fact has driven multiple Special Handling deputies—including Seth Tunstall, Ben Garcia and Bill Grover—to cite the Fifth Amendment when they refuse to testify in criminal cases. On prior occasions, they’d been caught committing perjury, but Rackauckas ignored their transgressions because the lies benefitted his office.

In January, U.S. District Court Judge Cormac J. Carney opposed federal prosecutors’ attempts to block the defense in U.S.A. v. Joseph Govey—as with Prinzi, a suspicious minor drug case—from questioning their star witness, Bryan Larson, about his role in the snitch scandal. Larson took the Fifth in a state murder case when called by the defense. “Then he’s willing to testify when called by the government [in Govey],” Carney observed. “How can I keep that away from the jury? There’s an inference there is a government bias.”

The U.S. Attorney’s Office also didn’t want Tim Scott, Govey’s counsel, to question Larson about Special Handling Unit misdeeds and refused to surrender related records in the unit’s possession. Afraid of an adverse ruling, federal prosecutors dumped 75,462 pages on Scott just before the scheduled trial in February. Unamused, Carney dismissed that case.

But that document dump demonstrated the extent of the records law enforcement withheld from Sanders, who was forced at times to fight years for a handful of pages. In June 2016, Rackauckas announced locating a huge, buried cache of OCSD informant records and assured the public he would finally comply with his obligations to turn over evidence favorable to defendants. According to OCDA, those documents contained additional proof of deputies’ secret, illegal acts and courtroom perjury.

Time attests Rackauckas had no intention of behaving. For example, as the Weekly learned, Foster’s name is found throughout the impeaching records, but none of the defendants’ attorneys in this deputy’s five drug cases were alerted. Sanders isn’t pleased that Prinzi began last November without OCDA complying with discovery rules. He requested access to the hidden evidence. “[I] certainly get to question the credibility of this [deputy] when he’s the sole prosecution witness,” Sanders told Dolnick at a March 20 hearing. “The case rests and falls on whether you believe him.”

Acknowledging his office hasn’t given the defense Special Handling records tied to Foster, senior deputy DA Brian Fitzpatrick boldly argued that Sanders possesses “no evidence to impeach” the deputy and therefore should be blocked from asking him questions “far afield of the facts of this case.”

As that prosecution advances, OCDA stonewalling continues, with the 75-year-old Rackauckas parading around the county to win a sixth, four-year term in June. He’s telling voters he always acts honorably. The DA says Sanders is a liar and reporters documenting the scandal are lemmings. Goethals, a former homicide prosecutor and onetime Rackauckas campaign contributor, was “biased” for recusing him from Dekraai after the cheating emerged.

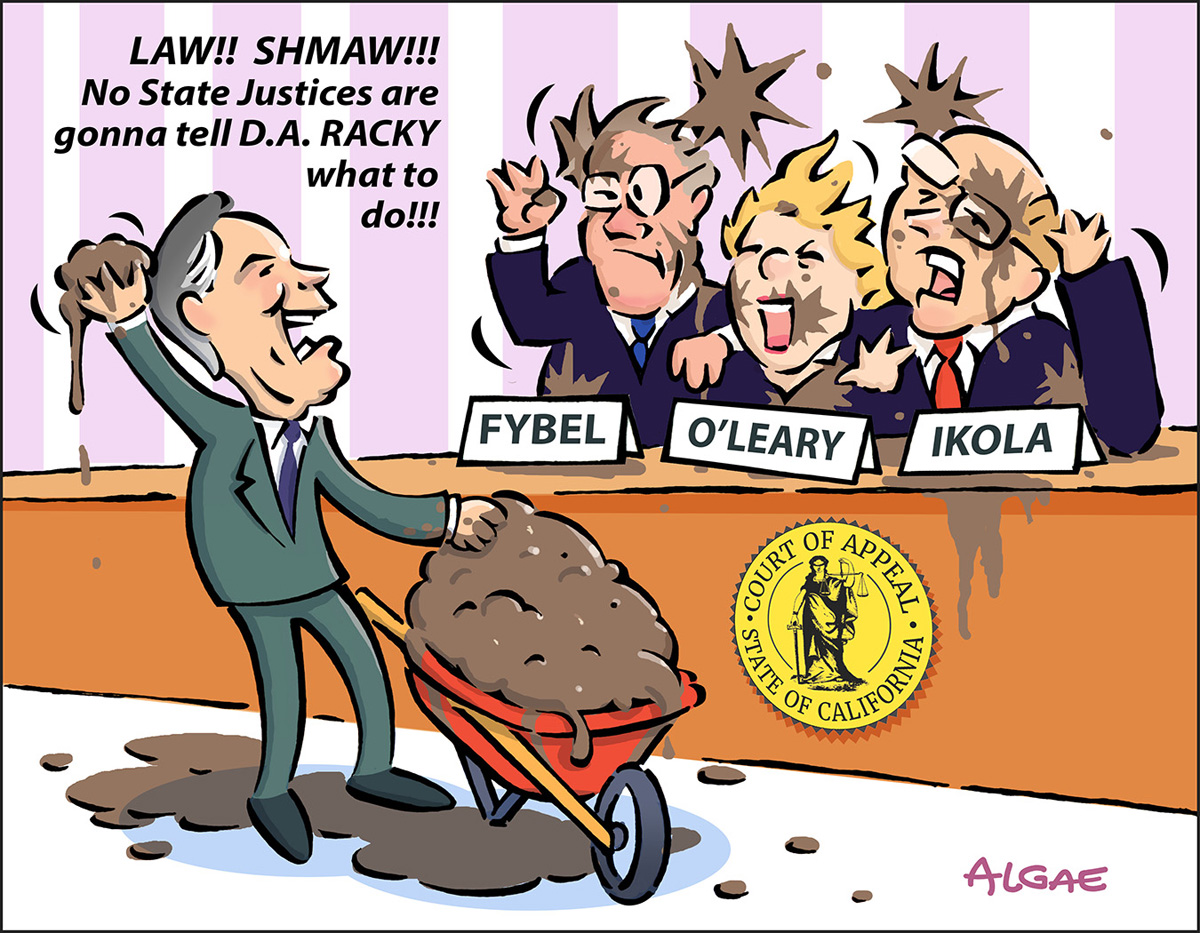

But the DA’s worst abuse is the attack on the California Court of Appeal. A three-justice panel of Richard Fybel, Raymond Ikola and Kathleen O’Leary rejected Rackauckas’ cries of innocence in November 2016. Upholding the Dekraairecusal, it ruled his misconduct in the informant scandal went “well beyond simply distasteful or improper,” but it is, to punctuate the point, a “grave” threat to the justice system. Rackauckas mocked the warning. At an election event, he labeled those justices biased, too.

The DA barked, “We are not backing down or walking on eggshells.”

No comments:

Post a Comment